During World War I, citizens — women, children and men unable to serve in the military — volunteered thousands of hours to support the war effort.

They worked in factories, bought war bonds, grew extra food in home gardens and canned it for storage. They made clothing for refugees. They rolled bandages, wrote letters for soldiers in hospital, made hospital gowns.

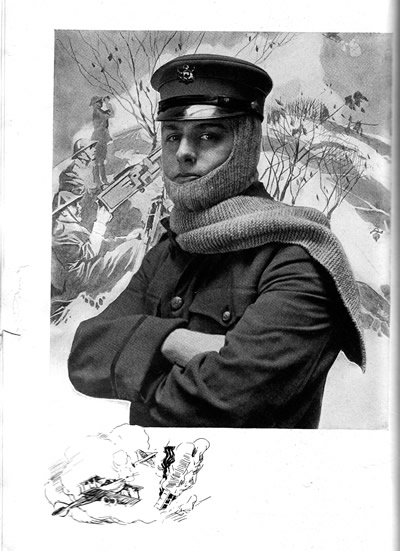

They donated material for “comfort packages” to be distributed to the troops on the front and to Allied prisoners of war. These comfort packages contained non-perishable food items, tobacco and cigarettes, and clothing, especially knitted articles such as gloves, mitts, scarves, cardigans, balaclavas and above all, socks.

Conditions in the trenches — the cold, the wet, the mud, the poor hygiene — made trench foot a constant danger. A fungal infection, trench foot could result in gangrene if left untreated. The only real preventative was for each soldier to have in his pack frequent changes of socks and another soldier to take turns with checking each other's feet. Many civilians at home knitted socks for relatives in the trenches, but a huge number spent the war years turning out thousands of socks for soldiers they didn't know.

Most women and girls already knew how to knit before the war, but once the call came out for socks many more learned. Children (both boys and girls) knitted at school or in Girl Guide and Boy Scout meetings. Beginners would start with simple squares to stitch together to make blankets for refugees displaced by the war. As their skill increased they would learn to knit socks.

Knitting communally helped make the work go faster as well as preventing the knitter from feeling isolated. But individuals who knit as part of a group would also knit alone at home and in spare moments in public — on the bus, at a meeting, while attending a class. Some were even able to knit while walking. Everyone was encouraged, as the slogan went, to “do their bit".

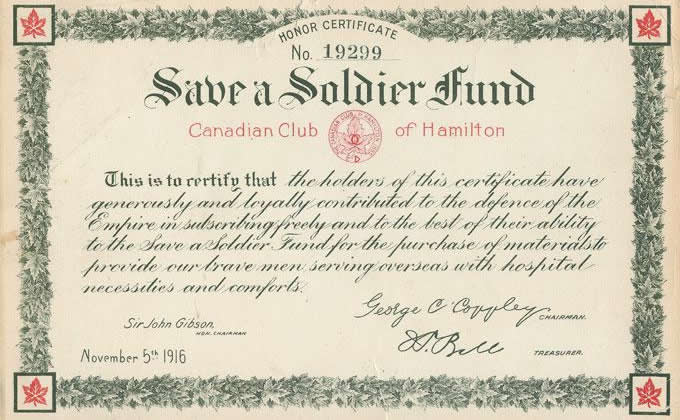

The photo at the left, from Queen's University Archives, shows a group of students at a School for the Blind using knitting machines to create socks. Children were particularly encouraged to participate in as many home front activities as possible, and many organizations offered small incentives or rewards, such as the certificates below, or badges, which would also be suitable for collecting.

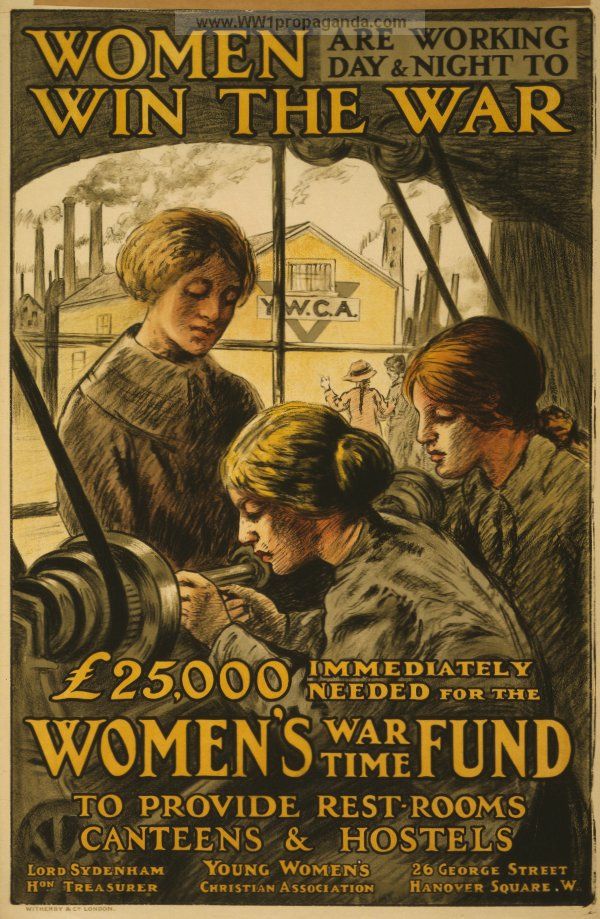

Many clubs and social organizations either added knitting to their regular activities or raised funds to supply wool and needles for knitters, or to ship comfort packages to the troops. Social historians point to women's involvement in these fund-raising efforts as a way in which ordinary women gained experience in grassroots organizing.

On the other hand, it has also been argued that the efforts of women who had been active in the women's suffrage movement before the War were now diverted into the war effort; organizations with substantial female leadership before the War gradually came under male leadership as regional organizations were consolidated provincially and nationally.

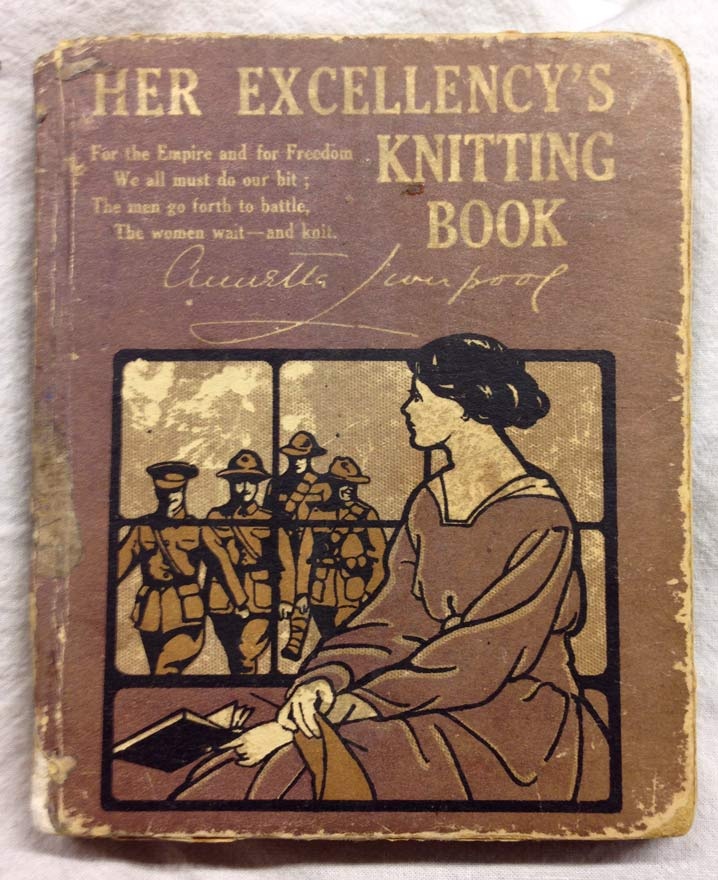

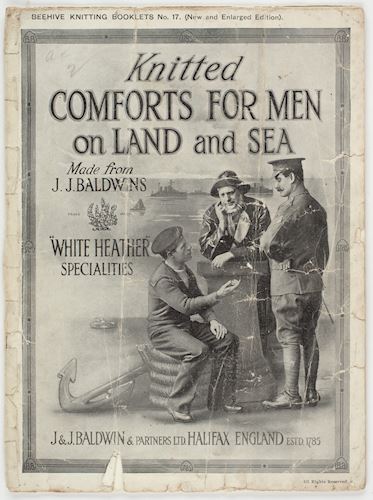

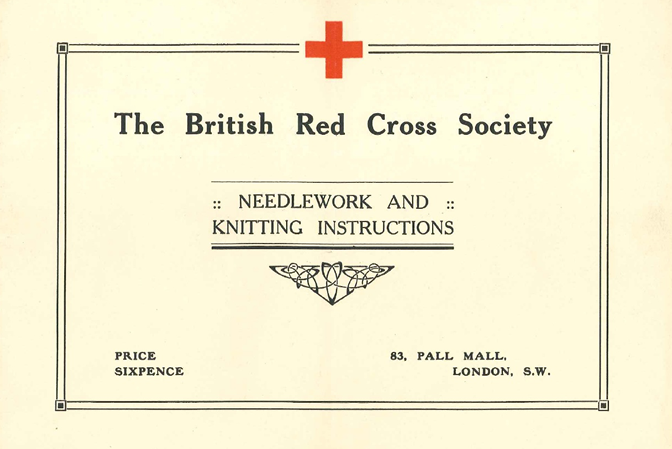

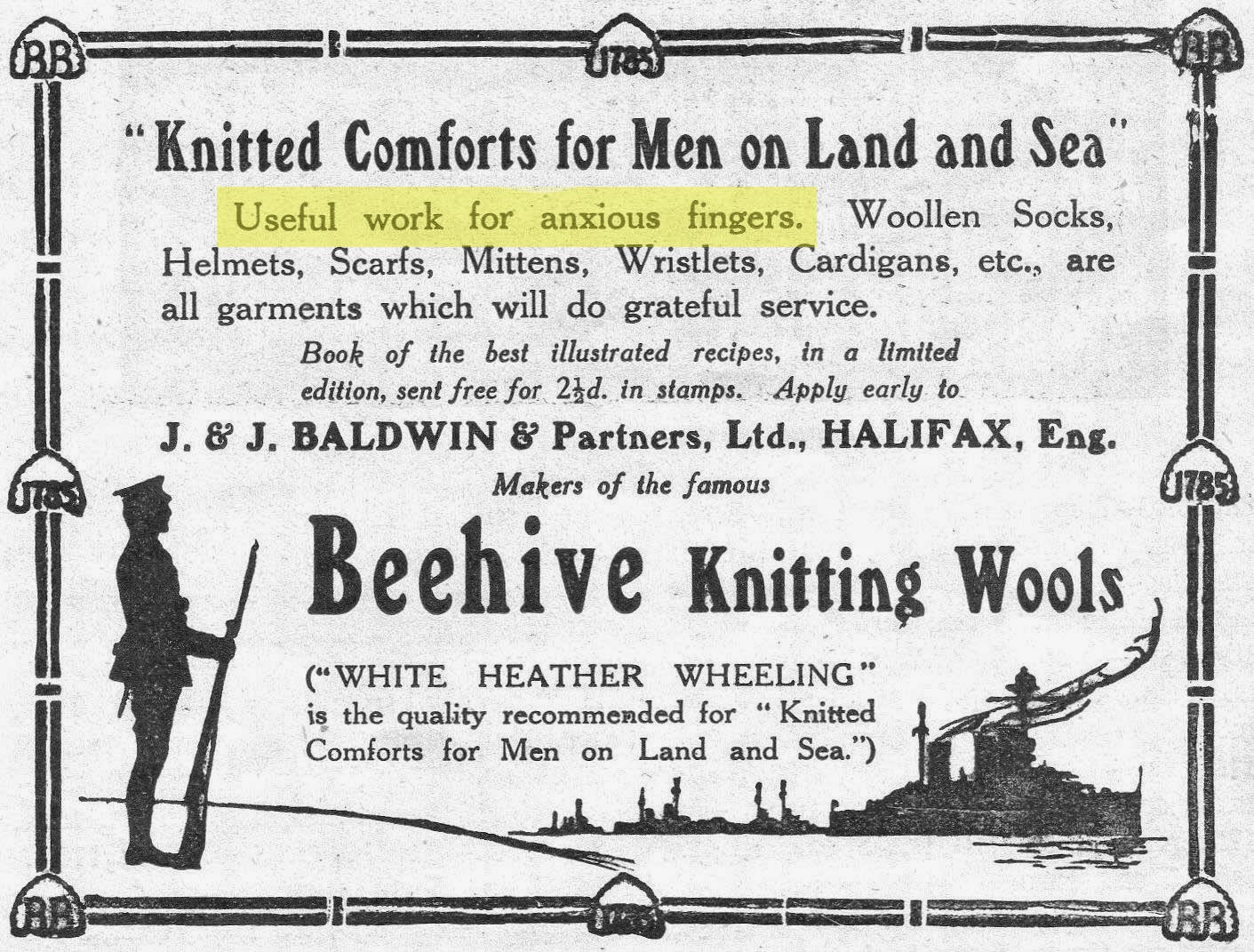

Organizations could obtain sock knitting machines but individuals produced socks the old-fashioned way, with four needles and a ball of yarn. At first knitters used pre-war patterns. Companies selling yarn also produced pattern booklets (promoting their own brands, of course). However, as the war went on, especially as so many people new to knitting began to participate, it became obvious that standardized instructions would reduce the amount of waste and ensure that all soldiers, no matter their size of foot, would receive a reliable supply of socks.

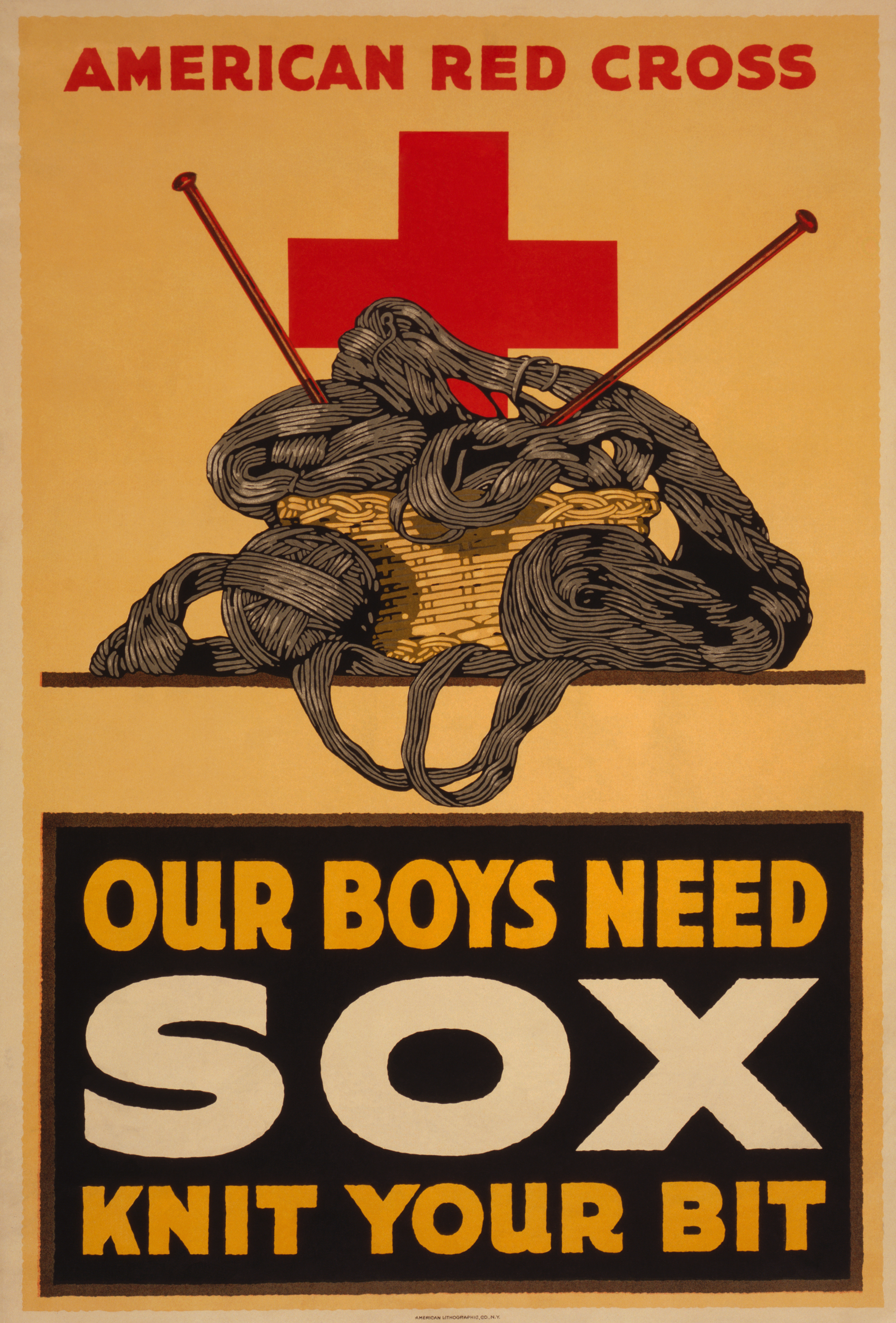

Organizations like the Red Cross produced and distributed standardized patterns. One set of standardized patterns specified a colour-coded stripe at the top of each sock in order to indicate the size: a white stripe for Small, a blue stripe for Medium and a red stripe for Large. Collections of knitting patterns in book form were produced in Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United States.

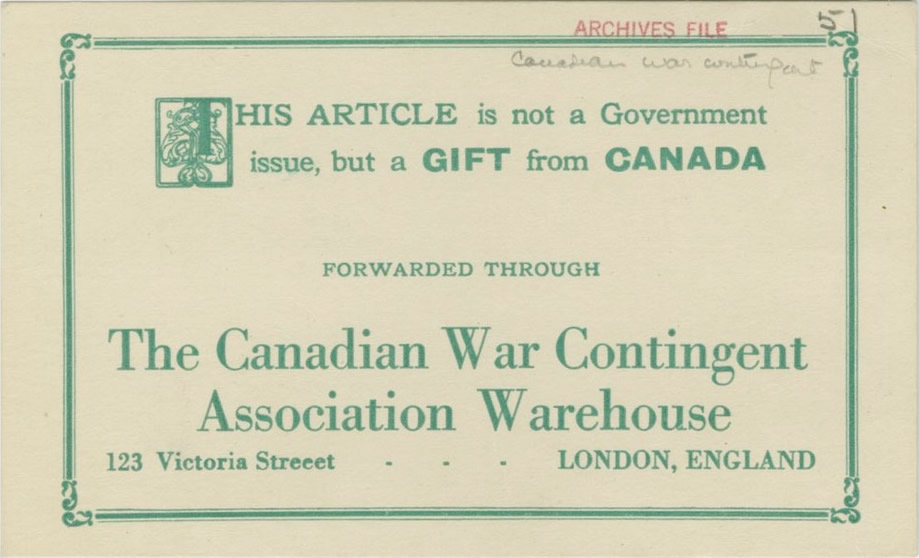

Organizations assembling comfort packages included a label to show that it had been produced by their group rather than the government. Knitters sometimes tucked a message into the finished garment for the soldier who would receive it, to remind him that he was in their prayers. A typical note might read: "Into this sock I weave a prayer, That God keep you in His love and care." Many recipients wrote a thank you note, sometimes addressed to the local newspaper in the knitter's home town. You can read one such letter, published in July 1918, here.

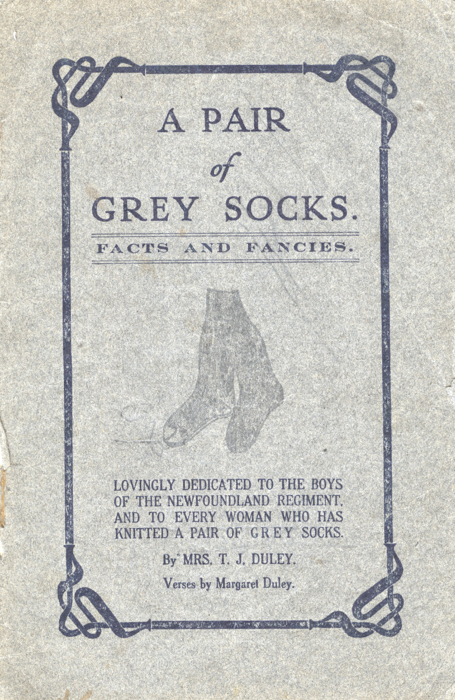

Knitters in Newfoundland and Labrador produced a vast number of garments for the men of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, and local authors Tryphena Soper Duley (1866 - 1940) and her daughter Margaret Iris Duley (1894 - 1968) produced a popular poem and short story in 1916 called “A Pair of Grey Socks: Facts and Fancies", about a knitter whose message tucked into a sock gave a wounded soldier hope to carry on (and how the two were married after the War).

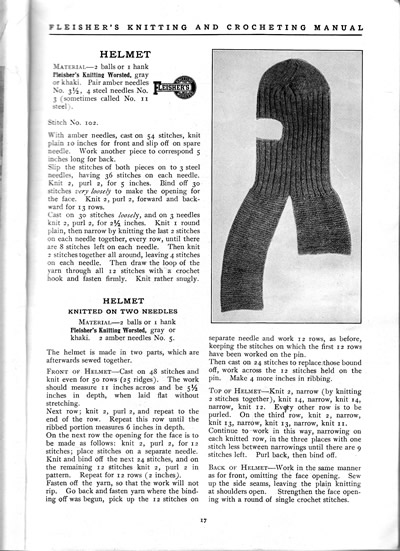

Even before America entered the war in 1917 many home knitters in the US were sending garments to the European front. Many of them would have used the patterns found in Fleisher's Knitting and Crocheting Manual. Fleisher's had been publishing this series since the late 1800s and WWI-era knitters might have used any of the 100- to 200-page volumes published annually between 1909 and 1918 to knit socks, scarves, cardigans, gloves and mitts. The sixteenth (1918) edition has a wide assortment of pieces specifically designed for servicemen overseas; click on the 1918 cover to the left for photos and patterns for a knitted Service Sweater and Helmet. Click on the Helmet photo and pattern below for detailed instructions for knitting that piece.

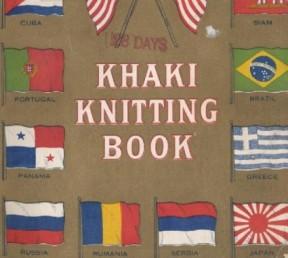

By 1917 American knitters could refer to Olive Whiting's The Khaki Knitting Book, which offered 50+ pages of instructions for knitted garments for servicemen (as well as for children and infants — presumably for refugee relief). You can view the entire booklet and its patterns online.

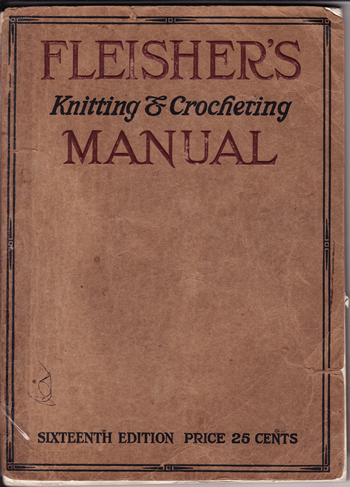

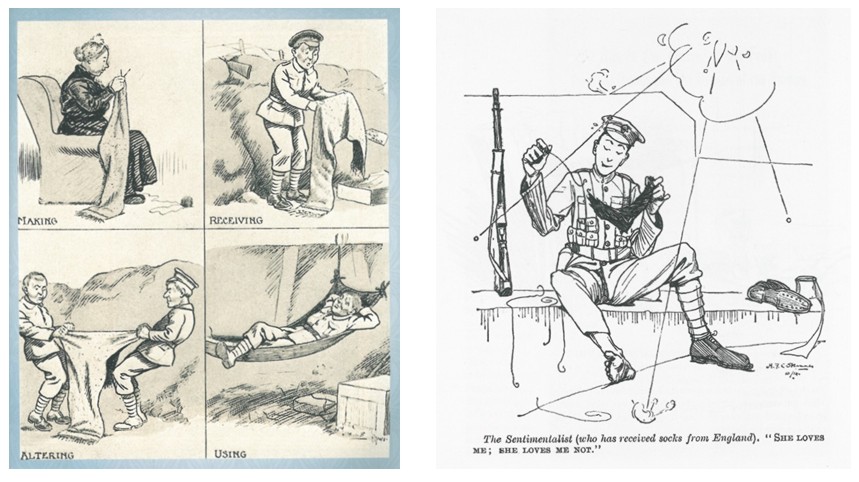

Despite the grimness of the war years, people still found it possible to poke a little gentle fun at amateur knitters. The Tattler ("Story of the Knitted Scarf” from The Tattler of 22 December 1915, right) and Punch ("The Sentimentalist” by Richard Brooks from Punch of 1 December 1915, right) produced the cartoons below:

And one Audrey J. Reid received the following verse from a New Zealand infantryman:

Life of a pair of socks

They are some fit!

I used one for a helmet

And the other for a mitt

Glad to hear

You're doing your bit —

But who the _______

Said you can knit?!