Children's Services at KFPL Before 1918

Our library started as a Mechanics Institute around 1834 and served as a reading room and lecture hall (and smoking room!) mainly for professional men. By 1851 it occupied two ground floor rooms on Princess Street, where Vandervoort's Hardware store is now located.

By 1910 the library had moved again, and was squeezed into a few rooms above a drugstore. Staff turnover was high. In the previous decade, five different librarians had come and gone:

- 1895 - Miss Olive Springs

- 1904 - R.R. Davidson

- 1905 - Miss Hildred Driver

- 1907 - Mrs. Beatrice Elliott

- 1908 - Miss M.G. Craig

In those days, children were not allowed to handle the books. One Kingston resident recalled that “as a child he climbed up the long staircase to the Association library. He handed his one book over a barrier to the librarian who enquired what topic interested him. The children were not allowed to choose a book! One of the children's secret pleasures was to keep on refusing to accept the librarian's choice until, in sheer exasperation, she allowed them to go to the shelves to choose a book for themselves.”

Aimee Kennedy, Chief Librarian

In early January 1910, the library and reading room was closed due to an outbreak of typhoid fever. Soon afterward, Mrs. Aimee Kennedy came to Kingston from her home in Ingersoll for a visit.

Although she had not intended to stay, she was persuaded to make Kingston her home and to accept the position of chief librarian. During her first year as librarian here, book circulation doubled. She retired forty years later, having developed the Kingston Public Library into one of the finest libraries in Ontario.

By 1911, the library was located at the corner of Bagot and Johnson Streets, where the Family Medicine clinic is currently located. At that time, the corner was occupied by an empty butcher shop. Miss Kennedy started lobbying politicians to fund a local “free library” so she could loan novels, magazines and children's books to everyone in town. At the time, the idea seemed quite radical!

The Introduction of Children's Story Hour in 1918

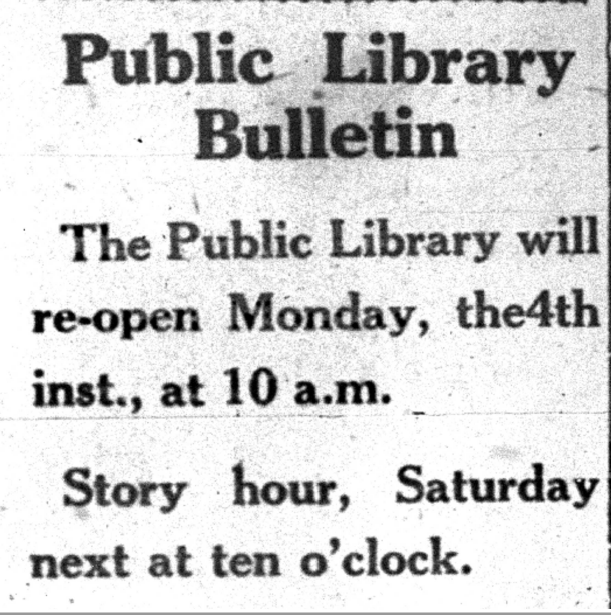

In 1918, Mrs. Kennedy introduced a children's story hour, and it has been continued ever since. You can learn more about that and Explore the Library Shelves, 1918-style.

Aimee Kennedy's Legacy at KFPL: 1921-1950

Three years later, Kingston's library had the highest per capita circulation in the province. This was as if every man, woman and child in the city had borrowed 5 books. Since the library was still in the old butcher shop, Mrs. Kennedy said this development was “not bad for a meat market.” In those days, there was still a fee for using the library, but a movement had started to make library services free for all residents.

In 1919, George Chown, registrar of Queen's University and library enthusiast, purchased the old Kingston Dairy School (Milk Trust Building) southwest corner of Brock and Bagot. He offered it to the city on the condition that a free library would be started, and that Kingston citizens would raise enough money to give the library a good start. He would add an extra $2000 to that amount (a good deal of money in those days!)

Within a few weeks, thirty-one local associations and societies had offered their support, and the City contributed $35,000. Unfortunately, Mr. Chown died before the project was finalized, but it had already gained momentum and was finally opened in 1925. Mrs. Kennedy thanked City Council for finally “wiping out the disgrace of being the only city in the province without a free library.”

Mrs. Kennedy continued to run the library for another 25 years. When she retired in 1950, a group of library patrons got together and commissioned a portrait by Grant Macdonald, which still hangs in the Central Library. She was succeeded as chief librarian by Miss Mildred Clow.